The year 2009 marked a watershed moment for al-Haq in its approach to seeking justice beyond the Israeli High Court of Justice. In Adalah v Attorney General (2009) al-Haq, Adalah and the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights petitioned the Israeli High Court of Justice to judicially review the decision of the judge advocate general not to launch a criminal investigation into the deaths of civilians and destruction to civilian property in the Gaza Strip during Operation Rainbow and Operation Days of Repentance during the second intifada.

The Court denied the petition on the grounds of generality and delay, outlining that the petition did not identify specific incidents of war crimes for investigation. Although the petitioners presented documentation from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, Human Rights Watch and the International Federation for Human Rights, the Court, somewhat arbitrarily, found that the claim did not have a “factual foundation.” The duty to investigate war crimes under the jurisdiction of the State comprises customary international law. Notwithstanding, the case marked yet another instance of the Court’s refusal to insist on criminal investigations reinforcing the Military Advocate General’s official policy of impunity for the deaths of protected Palestinian civilians during ‘active combat.’

For al-Haq, the ruling demonstrated the unwillingness of the Israeli High Court of Justice to order a criminal investigation. Israel has a duty to investigate, prosecute, punish or extradite individuals for international crimes. Moreover, the laws of war, the Geneva Conventions, obligate parties to search for persons alleged to have committed grave breaches of the Conventions regardless of the nationality of the accused[1]. Israel has signed and ratified the Fourth Geneva Convention, but has not incorporated the Convention into legislation making its application, according to former Chief Justice Barak, “bitterly disputed.” Less controversial, is Article 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which finds that “a party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty.”

Previously, in its report The Israeli High Court of Justice and the Palestinian Intifada: A Stamp of Approval for Israeli Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (2004), al-Haq questioned whether “the experience of Palestinians with the Israeli High Court of Justice and the policies followed by the Court so far require those working in human rights to seriously consider whether to resort to this body.” Prompted by the litigation delays in Adalah (the hearing was held more than two years after the petition was filed) and the arbitrary conclusion by the Court that the petitioners had failed to establish a “real suspicion” that criminal offences were committed, al-Haq once again considered its relationship with the Court and whether it might be more resource-effective to pursue justice in third states.

Al-Haq found recurring limitations to the pursuit of justice before the Israeli High Court of Justice including the Court’s deference to the military commander in cases of settlement construction,[2] military security[3], the impartiality of the judge in conducting criminal investigations into military operations, and the Court’s ad hoc application of proportionality and reasonability test[4] to dilute the substantive application of international humanitarian law. Cumulative obstacles led al-Haq to the conclusion that “human rights defenders in the OPT [Occupied Palestinian Territory] must now address the long-standing problem of the HCJ as a rubber stamp for illegal Israeli policies."[5]

In this regard al-Haq’s relationship with the Court remains fractious. The organization is mindful that in petitioning the Court there are insurmountable substantive and procedural hurdles in the Israeli legal system, which systematically deny victims of Israeli violations of international humanitarian law the right to an effective judicial remedy. That being said, the organization has not completely ruled out petitioning the Court in certain cases. For example, in two cases against the Wall[6] the Israeli High Court of Justice effectively reinforced the policy of expropriating private property for the construction of settlements and the de facto annexation of Palestinian territory while side stepping the overall illegality of the Wall and the failure to apply Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Nevertheless, in Mara’abe v, The Prime Minister of Israel and Ahmed Issa Abdallah Yassin v. The Government of Israel, the Court ordered a partial rerouting of the Wall (albeit not on the Green Line), thereby enhancing the quality of life of those immediately effected.

Taking the potential for rerouting the Wall into consideration, al-Haq decided to petition the Court, once again, on behalf of the villagers of Al Nu’man. Although the village is located within the Jerusalem municipal boundaries, the Municipality of Jerusalem and the Israeli Ministry of Interior issued the residents West Bank IDs and refused to supply basic services, such as electricity, food and water, to the village. The village is completely surrounded by the Wall and residents must pass through a military checkpoint to enter and exit the village while non-residents are denied entry. The restrictive impact on the delivery of food supplies, access to educational facilities outside the enclave, and deprivation of healthcare, which can only be accessed outside the enclave, together caused conditions that would lead to the gradual expulsion of villagers from the area. For al-Haq, the depth of the human suffering experienced in Al Nu’man, outweighed any reservations about reinforcing the illegitimate determinations on the legality of the Wall, by petitioning the Court. Notwithstanding, the Court denied the rerouting of the Wall and the issuing of new residency permits.

While al-Haq will sporadically petition the Israeli High Court of Justice, the organization’s primary focus is on third party states. Accordingly, al-Haq, noted its intention in Adalah to have recourse to foreign courts in the absence of a domestic remedy, an avenue regarded by President D. Beinisch as “a veiled ‘threat’.” Adding to the discussion, Justice E. Rubinstein proposed that any exercise of universal jurisdiction was designed to delegitimize the State of Israel. However, despite vehement opposition to the pursuit of justice in foreign courts, al-Haq considered this to be the best option going forward. Somewhat ironically, the Court added, “If the petitioners leave this court with empty hands, it is only because they took the wrong path, and therefore did not reach their objective.”[7]

In 2013, al-Haq’s advocacy in the Netherlands forged a new path, resulting in the Dutch ASN Bank which specializes in socially responsible investment, of its shares, divesting from Veolia, a French company accused of complicity in Israeli war crimes. Subsequently the Stadsregio Haaglanden municipality decided not to award a lucrative transport contract to Veolia`s subsidiaries in the Netherlands. Similarly, the filing of criminal charges by al-Haq in the Netherlands against the Dutch company Riwal contributed to the decision of Royal Haskoning DHV, another Dutch company, to terminate its involvement in the design of a wastewater project in occupied East Jerusalem, absolving the corporation from complicity in international war crimes and potential domestic prosecution.

Ultimately, al-Haq remains hopeful that in the future cases like Adalah will be referred by the Office of the Prosecutor to the International Criminal Court for investigation. Despite the recognition of Palestine by the United Nations General Assembly as a non-member State, politically, it would appear that the Office of the Prosecutor is reluctant to open an investigation until Palestine ratifies the Rome Statute. The ruling in Adalah demonstrates Israel’s unwillingness to open criminal investigations, which alone should trigger admissibility to the International Criminal Court under Article 17. However, the International Criminal Court is not an absolute panacea for ending impunity. Article 25 limits the jurisdiction of the court to “natural persons” excluding cases on corporate complicity or state responsibility.[8]

[This article was originally published in al-Majdal, Winter 2013-2014 edition.]

------------

1] Similarly the Convention Against Torture obligates state parties to “immediately make a preliminary enquiry into the facts.” Prosecutor v. Furundžija, Case No. IT-95-17/1-T,Judgement, Trial Chamber, 10 December 1998, para. 156.

[2]HCJ 2056/04, Beit Sourik Village Council v The Government of Israel et al., judgment of 30 June 2004, Paragraph 32; Mara’abe et al. v The Prime Minister of Israel et al,H.C.J 7957/04, paragraph 22.

[3]HCJ 1960/07 Al Haq et al. v. The Prime Minister et al. (July 9, 2008), paragraph 41-42; Al Haq, Al-Nu’man Village: A Case Study of Indirect Forcible Transfer (second edition, 2010)p. 40.

[4]D. Kretzmer, “The Law of Belligerent Occupation in the Supreme Court of Israel” Volume 94, Number 885 Spring 2012, p. 229; Similarly, Koskiennemi, argues that by using an administrative proportionality test in for the application of the laws of armed conflict, the military commander is placed in the position of the sovereign, which is at odds with the de facto nature of the military administration. Martti Koskienniemi, “Occupied Zone – A Zone of Proportionality” Transcript of Paper delivered at "Forty Years after 1967:reappraising the Role and Limits of the Legal Discourse on Occupation in the Israeli Palestinian Context." Koskienniemi argued, “The unease with the Israeli High Court’s turn to proportionality – as with that branch of humanitarian law tout court – relates to the manner in which it projects the occupation authorities just like any legitimate government situated anywhere.” The tests have been applied in Ahmed Issa Abdallah Yassin, Bil’in Village Council Chairman v The Government of Israel, HCJ 8414/05, paragraph 30; The Beit Arieh Matter: HCJ 9055/05Maccabim v. The Government of Israel (January 9, 2006); HCJ Har Adar Local Council v. The Ministry of Defence(September 10, 2006); HCJ Davka Co. Inc v. The IDF Military Commander, (December 31, 2008); Al-Haq, Legitimising the Illegitimate? The Israeli High Court of Justice and the Occupied Palestinian Territory (2nd edition, 2010).

[6] HCJ 2056/04, Beit Sourik Village Council v The Government of Israel et al., judgment of 30 June 2004; Mara’abe et al. v The Prime Minister of Israel et al, H.C.J 7957/04. Here the Israeli High Court of Justice judicially reviewed the decision of the military commander to route a Wall for ‘security purposes’ inside the Palestinian side of the Green Line, thereby expropriating private Palestinian land, and depriving Palestinian villagers of their freedom of movement, while protecting Israeli settlements built in violation of Article 48 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

[7]Ibid, [17].

[8] Palestine should also deposit a declaration accepting the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, as a more suitable forum to hear cases on state responsibility.

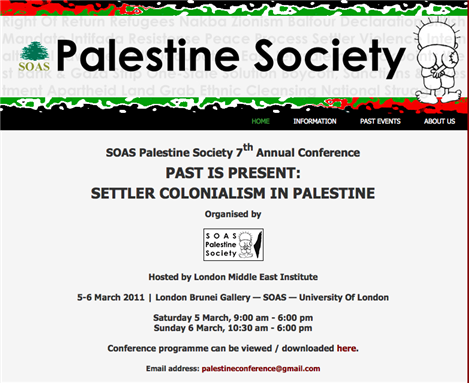

![[Palestinian children run near the Israeli West Bank barrier. Image by Justin McIntosh, via Wikimedia Commons.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/800px-Palestinian_children_and_Israeli_wall.jpg)